Caution: some artwork may not be appropriate for some children.

Every year in the creep to Halloween, a handful of journalists, bloggers, and podcasters play a well-meaning yet dubious trick on their audiences. They write or republish stories — unedited and unvetted for the most part — that use unquestioning language to unequivocally connect the objects we associate with witchcraft with the tools of the medieval and renaissance European brewer. Most brewers at the time were female and a great many females were brewers; a lot of them sold the surplus from the low-alcohol beer they brewed to nourish their families for the fewest of coins and the minimum of autonomy.

Brooms, cats, cauldrons and pointy hats all had their place. But did they spell the ruin of these “brewsters” and “alewives?”

The media pieces accurately explain that the forces of politics, economics and religion often “conspired” to suppress classes of people, women among them, and that brewsters, with their relative independence, threatened the social order. Enter brewster-as-witch smear campaign to literally kill them off.

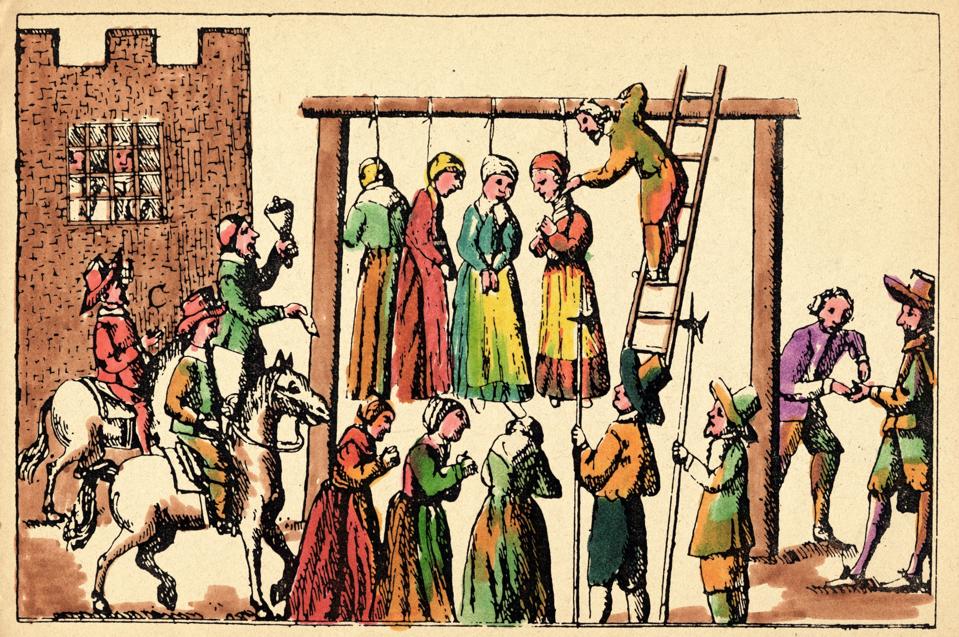

Execution by hanging of four witches. Colored engraving from ‘Law and Custom of Scotland in Matters … [+]

Getty Images

Though the storyline makes sense, it’s very likely a fairytale or at best “inspired by a true story.” Ireland-based beer historian Dr. Christina Wade, who’s excruciatingly researched the intersection of gender and beer in medieval northern Europe, convincingly argues that enough dates and places fail to match up for it to unfold that neatly.

“These arguments aren’t historically accurate. At all,” she writes on her blog, Braciatrix. “Hello, my name is Christina, Crusher of Myths, and today I’m here to refute the idea that modern pop culture depictions of witches are rooted in the dress and culture of either medieval, or 16th century alewives.”

To provide a little more context, here’s an edited excerpt from my book, A Woman’s Place Is in the Brewhouse: A Forgotten History of Alewives, Brewsters, Witches and CEOs. The chapter is “Strange Brew: Did Renaissance Brewsters Practice Fermentation . . . Or Witchcraft?”

The History Channel estimates that European authorities hanged or burned alive up to eighty thousand accused witches between 1500 and 1660 (some sources tabulate up to two hundred thousand for approximately the same time period), with Germany massacring the highest number per capita and Ireland killing the fewest. It formed part of a mass control and terror campaign the Roman Inquisition, the Catholic Counter‑Reformation against Protestant reforms, and the fledgling professional class of male doctors and lawyers waged against a formerly feudal and newly liberal population as they sought to consolidate their power and redefine the social structure. Twentieth‑ and twenty‑first‑century scholars credit the rise of capitalism to their efforts.

(Original Caption) Picture shows a witch hanging in England in teh 17th Century. Undated woodcut.

Bettmann Archive

“Is it a coincidence that the image of medieval brewsters so closely resembles the popular image of a witch, or was foul play perpetrated by persons who wanted to malign female brewers in an era when witch hunting was rife?” writes Jane Peyton, an alcohol historian and Britain’s 2014 Beer Sommelier of the Year, on her website, School of Booze.

The social structure increasingly stacked up against brewsters and alewives in the early modern era, with literature portraying them as sorceresses and the church preaching against the evils of alcohol and the female purveyors who lured men into sin. “If alehouses were ‘the devil’s schoolhouse,’” writes Judith Bennett in Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600. “Then women were the devil’s schoolmistresses.”

Let’s survey the evidence that suggests brewsters form a basis for our conception of witches.

Cats: Considered a familiar that accompanies a witch, cats made themselves valuable staples in the brewster home by devouring the mice and rats who fed on sacks of stored grain.

The pointy hat: Alewives in some regions donned it when they went on excursions to the market so potential customers could spot them above the crowd.

The broomstick: In some areas, regulations required the alewife to post an ale stake, a long stick adhered to twigs, which might have doubled as a broom, above her door to signal to customers and government regulators that she had beer to sell.

The cauldron: This is where the magic happened—literally. A massive cauldron of wort bubbles when it boils over a flame froths rabidly as it ferments.

For many thousands of years, a mostly illiterate European populace ascribed fermentation to magic.

Witches roasting and boiling infants, 1608 (19th century). Copy of an illustration from Compendium … [+]

Getty Images

It wasn’t just brewers, saints, and goddesses practicing the magic of fermentation. Up to and through the Renaissance, Europeans of all stripes used herbs and incantations for natural healing and other purposes—it was all they had. As schooling formalized, girls, whose household duties kept them from attending, couldn’t access this training. While young men earned degrees in the medical arts, increasingly Christian societies shunned the natural healing arts and the women who plied them.

“‘Wise women,’ herbalists, and old women have been looked on with suspicion in many cultures throughout millennia, so brewsters joined this group where superstitious, uneducated people considered such people to be ‘the other,’” explains Peyton in an e‑mail.

There’s little, if any, historical evidence directly linking real brewsters to witch trials. A project to identify and map women tried as witches in Scotland, home to an intense witch hunt between the late sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries, turned up no direct correlation, and according to Christina Wade, a study of the assize records in Essex, England, between 1560 and 1680 found only one woman with a listed connection to a professional brewer—her husband.