When Trey Zoller founded Jefferson’s Bourbon in 1997 in the heartland of bourbon, Louisville, Kentucky, his hometown, he knew he was taking a chance. But that didn’t matter. All he knew was that he wanted to try his hand at crafting the spirit that he had heard about since his youth and that had been labeled by the United States Congress in 1964 as a “distinctive product of the United States.”

Eschewing the traditional path of becoming a distiller, he instead embraced a radical idea; he would focus on blending bourbon while continually tinkering with different methods to mature them. His ideas were not highly popular in what was then an inflexible industry. Still, he didn’t care, and his penchant for experimentation earned him the moniker the “Mad Scientist” of bourbon.

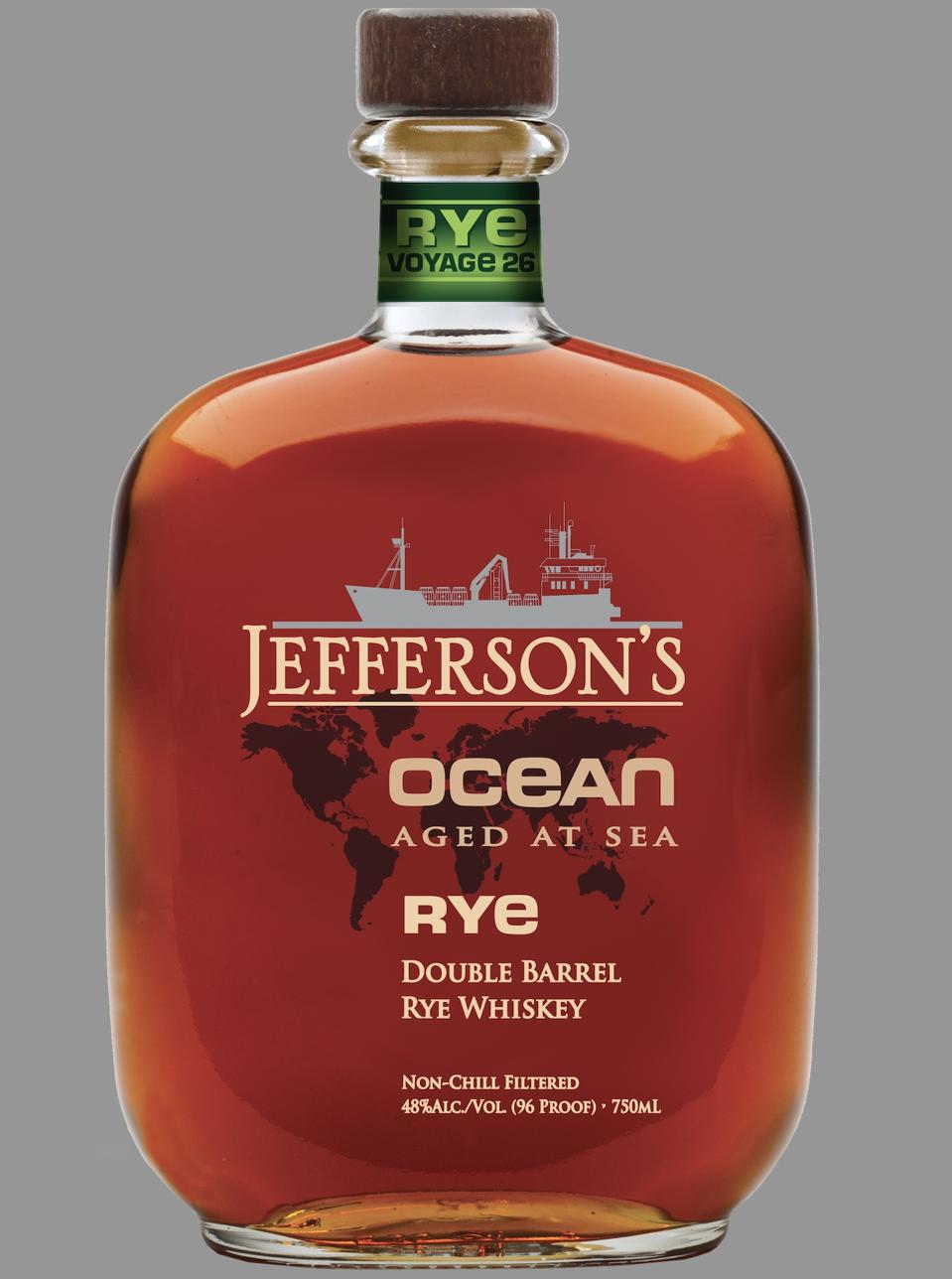

He recently released the 26th iteration of his highly popular Jefferson’s Ocean. It’s a unique bourbon that he launched in 2012 that sends a different batch of bourbon traveling across the seas, creating something wholly different each iteration. While afloat, the barrels reside inside a special shipping container that uses the natural motion of the ocean and heat of the equatorial regions to create a different maturation process each time.

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing for Zoeller, and the lessons he has learned apply to most businesses these days. We reached out to him to learn more about his story and how he was able to steer a successful path forward. His responses have been lightly edited.

Your idea to blend whiskey was unheard of when you started, but now many brands do it. What led you to do something so unorthodox?

I realized if I did do it like the other people up the street, I didn’t have a shot for several reasons. One, you know, there were only eight urban distilleries left in Kentucky in 1997. They had built up a considerable inventory because demand had decreased over the last 25 years. So they could undercut me every day of the week, and they had the inventory to bury me. Plus, they had their long heritage to lean on to sell their product, something that I, as a newcomer, didn’t have built up.

So, I looked long and hard at the industry and decided to try and evolve it. I thought that would be the easiest way to make my products stand out since everybody at that time only wanted to make bourbon the same way. There was no small batch and craft mentality in the industry then. Everything was geared towards mass production.

What pushback, if any, did you get when you started from the bourbon industry?

I began to buy barrels from everybody, and they thought I was crazy. They would tell me the same thing, that the heart and soul of bourbon comes from the maturation process, which I agreed with, yet everybody did it the same way. I started looking at bourbon and thought, why not change the environments that bourbon matures in from barrels to agitation and everything in between and really push the boundaries of what it can be and enhance it.

I decided to approach it from a winemaker’s point of view, to experiment with blending different products to create something unique. No one wanted to talk about blending at all then, it was a dirty word, but I stuck to my vision and kept at it. I would marry products from different distilleries and lots and ages to make something that was complex and sophisticated. I was and still am passionate about crafting something wholly unique.

What were the first few years like trying to get retailers to try something different?

Honestly, for the first ten years or so, no one really cared much about what I was doing because no one was thinking about drinking bourbon. They were just drinking whiskey. At times it seemed like I couldn’t give my products away. I thought about just giving up and walking away. But instead, I focused on selling into other markets and pursued any idea I had to bring cash in. I even launched my own energy drinks for a while. I just loved bourbon too much and knew my bottles would take off one day.

Everything started to change around 2008 once smartphones came on the scene and people were able to start digging into the history of their drinks. Suddenly, people started geeking out, and the bourbon market exploded almost overnight. The oldest native spirit in America suddenly became very cool to drink, and everyone was paying attention to how it was made. Over the next four years, you started to see more bottles of bourbon pop up on the back bars as consumers began looking for variety. Since I had been hustling for the last decade, I had credibility and was able to get my products in bars and stores.

Another way you ignored conventional wisdom was forgoing building a distillery and instead focusing on blending. Why did you do that, and why have you not built your own distillery yet?

I didn’t have the money to build a distillery and lay down product for years until I could sell it. That’s a terrible business model that ties up your cash and takes focus away from your sales and marketing, something you must execute well to succeed because I promise you your competitors are doing that. So instead, I decided to take what was available, young bourbon in barrels from larger distilleries, pivot with it, and try to make it better by experimenting with the maturation processes. That mentality continues to this day. I have never built a distillery. Instead, I work with Kentucky Artisan Distillers, where our tasting room is located, and use products they distill.

As someone who takes chances, what have you learned from your failures?

I have had my fair share of disappointments; it’s just the price I have had to pay to learn what works and what doesn’t. There is a tipping point or an apex you reach with every bourbon in the maturation process where it hits its peak and then starts coming down. I have had some fantastic barrels when I tasted them, so I tried to add a bit more age in, and the next time I sampled them, the extra time had overtaken them, and the flavor I loved was gone. Or I have blended something I thought would rock, and it didn’t. You won’t succeed if you are unwilling to fall down or dump some product in my case.

Is there any idea you won’t embrace?

I won’t do anything that cheats my bourbon or cuts corners, like adding in flavors. I come from a family with a long history with bourbon. I was taught to respect Kentucky’s native spirit. I’m always tipping my hat to the tradition of bourbon but continually trying to expand what it can be. I don’t want to jump the shark and have turned down some crazy ideas for my bourbon. If something seems like it might make something cool while grabbing the public’s attention, I will look into it, but I don’t want to do anything cheesy. I need to stay true to the standards that I have built at Jefferson’s.

How have you maintained your brand’s focus since the Pernod Ricard purchase in 2019?

I had to learn how to work within Pernod Richard to ensure that Jefferson’s and myself stayed true to ourselves. Learning how to work inside a larger framework can sometimes be frustrating, but in the end, we both want the same thing. Luckily staying entrepreneurial was one of the things that they wanted from day one, so it’s been a good partnership. In the next few years, I think you’ll see we’re going to have some genuine game-changing innovations not just in the bourbon category but the whiskey category as a whole. I think some pretty exciting years are coming up.

The latest version of Jefferson’s Ocean Aged At Sea series features its first ever rye bourbon.

Jefferson’s Bourbon

Tell us about the latest Ocean Aged at Sea, your first rye.

I like rye quite a bit. It’s very different than other bourbons because it has a sharpness that comes up, and then it gets dry and allows other components to surface. By putting it on the ocean, I thought we would get more texture out of it, and we did. An excellent viscosity naturally formed when the heat caramelized the sugars in the barrel.

To round out the flavor, we took mature four- and five-year-old rye and put it into new barrels- 75% we char three barrels and 25% toasted. We sent it off to 30 ports on five continents and crossed the equator four times. We bottled it up at 96% proof which gives it a lot of flavors that just explode out. It’s a true sipping bourbon.