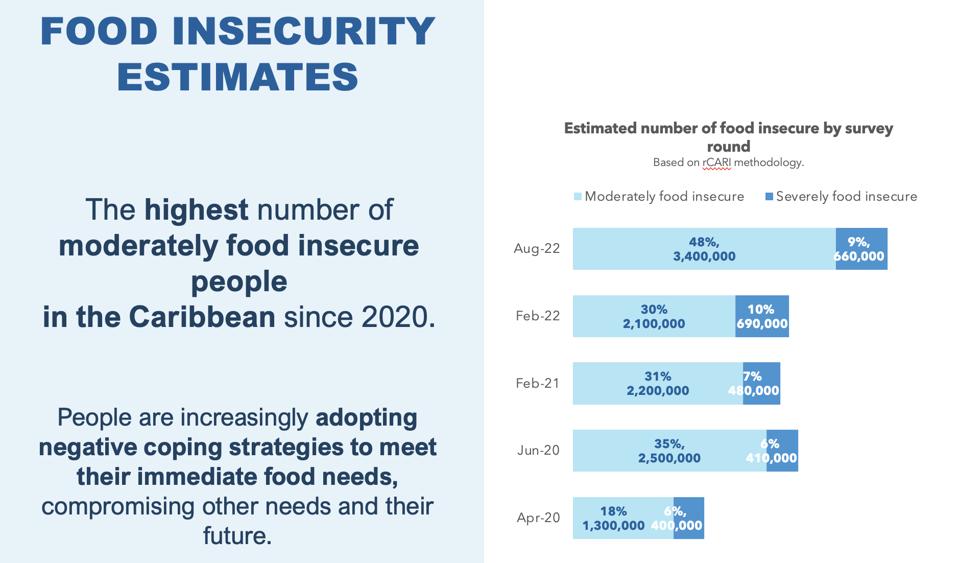

In the English and Dutch-speaking Caribbean, a region of some 22 countries, the compounded effect of more than two-years’-worth of global crises has caused surges in the cost of living, driving a 46% increase in moderate to severe food insecurity between February and August 2022— the highest rate since 2020— leaving 57% of the population struggling to put food on the table.

These are the findings of the fifth installment of a regional survey conducted by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and The Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA).

In 2020, CARICOM and WFP began tracking the impact of COVID-19 on food security and livelihoods across the region through the CARICOM Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security and Livelihoods Impact Survey which was administered in April 2020, June 2020, February 2021 and February 2022, with the socio economic impact of the current cost of living crisis being added to the most recent August 2022 analysis.

As with prior installments, experiences with food insecurity were assessed using WFP’s Consolidated Approach for Reporting Indicators of Food Security (CARI), methodology which placed respondents into categories on a food insecurity scale, that takes into account the interplay of a number of variables associated with food consumption, livelihood coping strategies and economic vulnerability— with the most extreme category being labeled “severe.”

Regis Chapman, WFP Representative and Country Director for the WFP Caribbean Multi-Country Office, explains that coping strategies employed by individuals are key in assessing their degree of food insecurity.

“Severely food insecure households struggle to put food on the table every day or have to employ coping strategies that undermine their ability to do so in the mid-term just to meet the needs of that day,” he says, outlining that some these coping strategies when employed by significant numbers in a population also have the potential to negatively impact socio-economic development on a macro-level.

According to the findings of the survey, 54% of respondents reported reallocating funds from essential needs such as health and education to food as a coping strategy, while 83% reported having to dig into savings to put food on the table.

“These negative coping strategies are unsustainable, and we fear that these short-term measures will lead to a further increase in the number of people who are unable to meet their daily food requirements,” says Chapman.

The latest survey results estimate that 4.1 million people out of 7.1 million (57%) in the English- … [+]

In short, for a region that imports close to 100% of its energy, and up to 90% of its food, more external shocks could equate to disaster…

Meanwhile, the availability of fresh food has been declining for more than a year and a half and prices have been going up.

“We in the Caribbean have to reclaim our own narrative around food systems,” says Dr. Renatta Clarke, FAO Sub-regional Coordinator for the Caribbean.

Data from the Food and Agriculture Organization reveals that, in March 2022 food inflation in the region increased by 10.2% across 20 countries, as compared to March 2021, with Barbados and Jamaica recording 20% and 15% food price inflation respectively, and Suriname recording a whopping 68.3% food inflation rate.

Contextually, global food prices have been declining for five consecutive months, reaching their lowest level in seven months in August 2022, despite still being 7.9% higher than a year ago. (FAO Food Price Index)

And the proof is in the proverbial pudding, with 97% of survey respondents reporting higher prices for food items compared to 59% in April 2020, with almost all respondents noting significant increases in the price of gas (95%) and other fuels (94%).

On top of the tsunami of price increases, there have been equally dramatic livelihood impacts. Seventy-two percent of respondents indicated experiencing job loss or income reduction in their households, or having to resort to secondary income sources, up from 68% in February, while 72% reported an expectation that their livelihoods would be further impacted by COVID-related disruptions.

Not surprisingly, a lack of financial resources was cited as the primary reason (91%) for why more than half of respondents found it difficult to access markets.

But even those who indicated an ability to access markets have reported changes in behavior, such as consuming cheaper foods and smaller quantities, with 22% of survey respondents reporting going an entire day without eating in the 30-days prior to the survey, and 67% reducing the diversity of their diets as a coping strategy (up from 56% in February).

Tragically, the most widespread negative food consumption behaviors were primarily employed by the most vulnerable— lowest income households, younger respondents, mixed and single-parent households and Spanish-speaking migrants.

And regional anxiety around meeting expenses has been increasing across the board.

Joseph Cox, Assistant Secretary-General, Economic Integration, Innovation and Development at the … [+]

“For the first time in five surveys over more than two years, the inability to meet food needs, along with meeting essential needs, were top concerns for people (48%) followed by unemployment (36%),” says Joseph Cox, Assistant Secretary-General, Economic Integration, Innovation and Development at the CARICOM Secretariat.

As households continue to reel from the impacts of the pandemic, they are facing the interconnected challenge of meeting their food, energy, and financial needs.

CARICOM, WFP, FAO, CDEMA and other partners have been collaborating to increase resilience to shocks through stronger disaster management, social protection and food systems that are more effective, sustainable and responsive in meeting the needs of those most affected by crises.

And with more than two thirds of respondents expressing negative or very negative sentiments regarding their current financial situation, broad and aggressive approaches are critical in addressing the region-wide crisis.

“CARICOM recognizes that further interventions are necessary to reduce the level of need in the region and establish systems which facilitate sustainable access to nutritious food for all,” says Cox.

President Dr. Mohamed Irfaan Ali of Guyana with Prime Minister, Mia Amor Mottley of Barbados

Guyana has seized a leadership role under its President, Dr. Mohamed Irfaan Ali, in boosting food security at a regional strategic level, and ambitious plans are underway to reduce the region’s $4-billion food imports by a targeted 25% or $1.2 billion by 2025.

The plans have focused on the expansion of regional food production, while also addressing logistical issues that have been singled out by many as the primary reason for high import rates.

“Leaders in the region are actively engaging with decision makers across all relevant sectors to identify solutions for increasing food production and reducing import dependency within the region in order to reduce the cost of food,” says Cox.

Regional governments and NGO’s have also been addressing issues surrounding sub-optimal participation in the agriculture sector, nutritional improvement and redirection of regional consumption patterns while adapting to and mitigating climate change impacts, among a myriad of other food systems priorities.

“It’s not enough that we produce more food,” says Clarke. “We have to produce more smartly, based on a better analysis of where the market opportunities lie and making sure that we are sufficiently well organized to capitalize on these opportunities.”

Organizations such as WFP have been helping to directly address livelihood impacts by supporting and helping to improve and innovate national social protection systems, making them smarter, more responsive, and resilient in the face of crisis.

At a national level, from a social protection standpoint, more than one in five survey respondents reported receiving some form of assistance from their government in response to the impacts of the pandemic. However, investments in data are critical for the development of better social protection programs that include everyone, and particularly the most vulnerable. This has been one of the objectives of WFP support to regional institutions and national governments.

And there has been no better time to drive aggressive change.

The economic outlook for the food security of net importing nations such as those in the Caribbean has been influenced by shock-after-shock that has hit the most vulnerable the hardest; rather than following with response-after-response, the message is clear— resilience building is more important now than ever before.

“Information is crucial, because it helps us plan better to take better action,” says Clarke. “The information from this series of surveys has helped us to galvanize political action across the Caribbean and within the donor community to address vulnerability and food insecurity during this painful, protracted and increasingly complex crisis.”