In about a month, the Black Sea Grain Initiative agreement between Ukraine and Russia will expire. If it’s not extended, food prices and global shortages will rise. But with things going badly on the Ukrainian front, Putin may use grain as leverage.

Agreed to in late July, the Turkey- and U.N.-brokered deal allowed the resumption of exports from Ukraine through a safe maritime corridor of grain, other foodstuffs and fertilizer that had been disrupted by Russia’s blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports. The deal took some pressure off of world food markets even before shipments monitored by the initiative began leaving from three key Ukrainian ports (Chornomorsk, Odesa, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi) on August 1.

Ukrainian organizations, including its Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food, are keenly pointing out that November 19 will mark either a continuation of the 120-day agreement or a halt to Black Sea grain shipments if Russia does not agree to extend the deal. A red light from Putin to put pressure on Ukraine and the West would reverse what relief the limited flow of grain has provided and exacerbate the global food insecurity expected with smaller Winter-wheat harvests this season in Ukraine.

A non-profit organization of Ukrainian communication experts called PR Army has been calling attention to the approaching renewal date for the Initiative, urging the EU to help make emergency grain routes permanent.

According to PR Army, Ukraine’s total grain exports are down 48.6% so far in the 2022-2023 season compared to the previous season. As of June, only 14.2 million hectares had been planted with spring crops, which is 19.4 percent less than last year the non-profit says:

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Agriculture, 30 percent of the country’s farmland is occupied or unsafe. 160,000 square kilometers of land may be “contaminated” by land mines and other explosives… And while farmers are braving the danger to sow winter crops and complete the 2022 harvest, the projected decline in Ukraine’s food production due to the war is significant enough to raise the alarm.

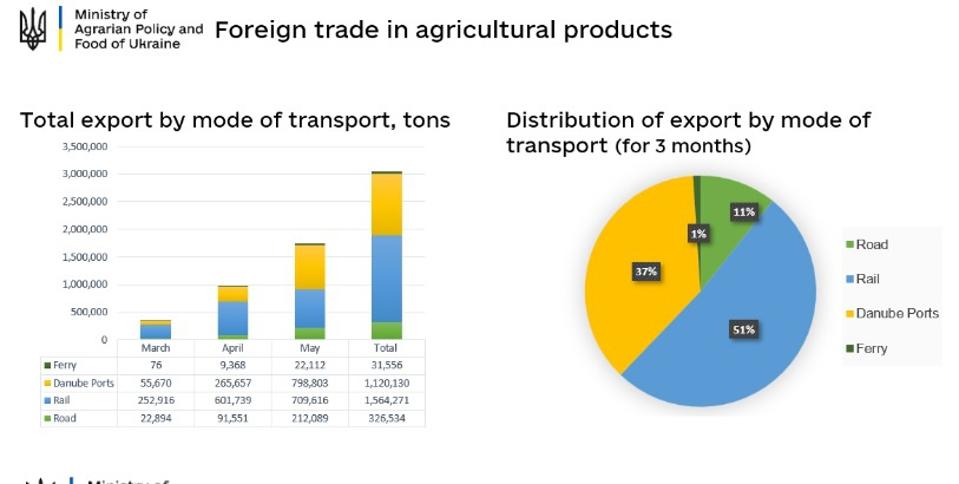

An infographic from Ukraine’s Agriculture Ministry shows the marginal increase in grain distribution … [+]

The ongoing information contest between Ukraine and Russia is obvious but there can be no question that Russia has harshly damaged Ukraine’s agricultural output, arguably stretching back to its annexation of Crimea in 2014. Caitlin Welsh, director of the Global Food Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), says the impact of the invasion on Ukrainian grain production and export will only fully be felt as 2022 winds down and 2023 moves on.

“Most of Ukraine’s wheat is winter wheat. It’s planted in the summer and fall, grows over the winter, is harvested the following summer then is exported. So the crop that was planted last winter and in the ground this summer is now being exported.”

Welsh adds that the latest numbers on Ukrainian grain from the USDA came out this week. They forecast Ukraine’s export of wheat at just under 17 million metric tons. The figure for 2021 was just under 21 million metric tons. Wheat production within Ukraine declined by about 20%.

The country has been “incredibly industrious” Welsh says in finding alternative routes for export and its farmers/producers have undertaken “brave” agricultural operations during wartime but emphasizes that less will be planted in Ukraine for harvest next year thanks to the War’s impact on the Ukrainian labor force (estimates say 20% of it is no longer active), farm equipment, storage and more.

PR Army asserts that Russia is “continuously smuggling” grain from occupied territories in southern Ukraine. It says Russia has illegally exported at least $530 million worth along with documented burning of crops and theft of grain and equipment amounting to more than $22 billion in lost potential income for Ukraine’s agro-industrial complex.

While the numbers may be hard to confirm, Welsh says that a recent Bloomberg report includes Russian claims that its agricultural exports will increase by 5 million metric tons thanks to the land it illegally annexed from Ukraine. Russia is the world’s largest wheat exporter and Welsh adds that it had a very good wheat harvest this year (projected to export over 39 million metric tons)

Welsh notes that Russia has been promoting a narrative that Western sanctions are to blame for reduced exports from the Black Sea which is “completely laughable” she says. Russia also stopped publishing data on its agricultural trade in April of this year. There is likely a motive behind the move to stop sharing data.

Putin has previously tied the grain export issue with the lifting of Western sanctions and could do so again. Russia is under obvious economic pressure and a return to the cessation of grain shipments from Ukrainian ports would put further upward pressure on world grain (and other agricultural output) prices.

Russia would benefit, financially secure in the knowledge that the United States and the EU will not likely sanction Russian agriculture or agricultural exports to prevent a spike in prices and food insecurity.

Ukrainian farmers harvest wheat working around an artillery shell crater in a field in the … [+]

In its short tenure, the grain shipment agreement has worked. Amir Abdulla, the U.N. Coordinator for the Black Sea Grain Initiative, notes that prices have come down five months in a row. The U.N. says its Food Price Index has decreased nearly 14 per cent from its peak in March of this year. Abdulla remains positive on the possible extension of the Initiative, expressing his hope that “with the UN’s mediation efforts, it won’t really be a matter for discussion.”

Ironically, Ukraine’s success on the battlefield – including the recovery of some agricultural land in the Donbas region – and its consequent pressure on Vladimir Putin may indeed make Black Sea exports a matter for discussion. With a record 345 million people in more than 80 countries currently facing acute food insecurity according to the U.N., the power Russia wields over Ukraine’s agricultural output – even as it loses territory – cannot be ignored.