On Thursday, Americans will pause to give thanks, a modern expression of the ancient tradition of harvest festivals that celebrate an abundance of food.

So, it is fitting then that today is World Fisheries Day, a celebration of the abundance of food that comes from the waters of our planet.

A thread runs from World Fisheries Day back in time to that first Thanksgiving: rivers are essential to abundant food. That was true in Plimouth Patuxet in 1621 and that remains true 401 years later.

Although we now associate Thanksgiving with turkey, researchers have concluded that a large proportion of the protein sources on that 1621 menu were harvested from local rivers, marshes, and river-fed estuaries. These included ducks, geese and swans, as well as oysters and eels (see below for some recipes inspired by these original dishes).

In fact, it is not even clear that turkeys were part of that first Thanksgiving, but ducks and geese almost certainly were, as waterfowl were both abundant during their fall migration and “easy to shoot” relative to turkeys, according to a written description of hunting at Plymouth (The Wampanoag arrived bearing five deer, so venison was also a big part of the meal).

And the menu items, such as corn, that came from the Pilgrims’ gardens? These had been fertilized with alewife or shad, migratory fish that crowded the rivers as they swam upstream to spawn during the spring planting season.

Eels traveled in the opposite direction and were particularly abundant during the late fall. Adult eels, which live and grow in streams and rivers for 10 to 30 years, swim downstream toward the ocean to ultimately spawn in the Sargasso Sea. During this downstream migration, the eels were easy to catch and the Pilgrims noted that, during the fall, “We can take a hogshead [a large cask] of eels in a night with small labor.”

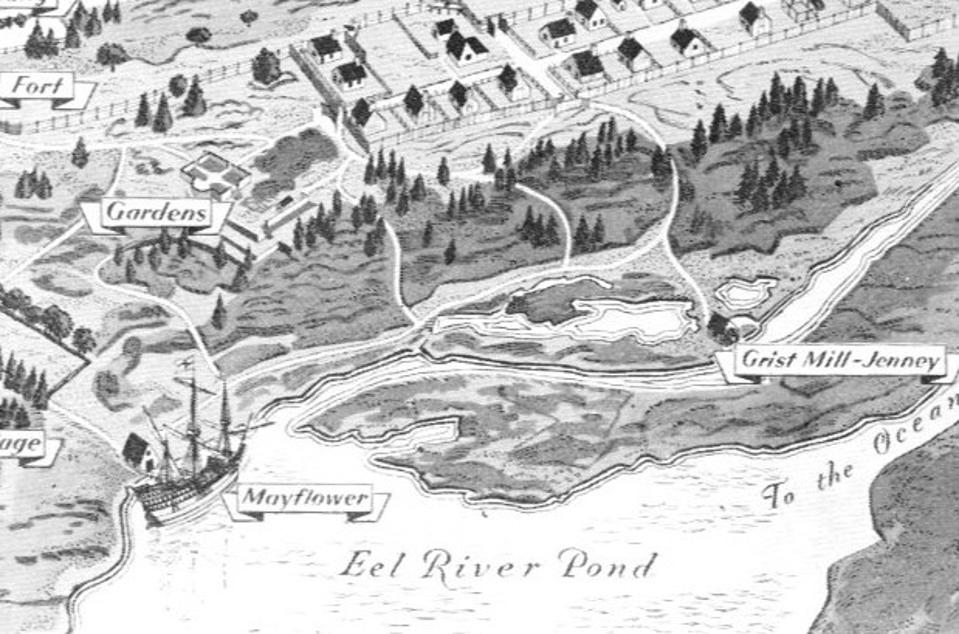

Reflecting the importance of this migratory fish, the Pilgrim’s original Plymouth settlement was built along the Eel River. In fact, these abundant fish—fatty and high in protein—were so important to the survival of the Pilgrims in those early years that writer James Prosek asks, “Why isn’t eel, instead of turkey, the symbol of colonial resilience and gratitude?”

A map made for the reconstruction of Plymouth settlement, showing its location on the Eel River and … [+]

The lack of appreciation of the importance of river-harvested eels to the Pilgrims mirrors a common challenge that persists today: the lack of appreciation for the importance of rivers for global food production.

Take World Fisheries Day. When I searched for some information on the day to link to, the first site that came up was sub-titled, “From sea to table.” No doubt, marine fisheries are a crucial food source, but freshwater ecosystems (rivers, lakes, wetlands) represent about 13% of all global fish harvest. Moreover, because a high proportion of freshwater fish harvests take place outside of established markets and monitoring, scientists believe that freshwater harvests could represent something closer to 20% of all capture fisheries. (And note this is coming from less than 2% of the earth’s surface, compared to the 75% that the oceans occupy).

Further, the influence of rivers is not limited to their own channels. They spill out into the ocean, dropping the sediment they’ve been carrying to create deltas and pulsing nutrients into estuaries and nearshore marine waters.

This marriage of river and ocean is particularly fecund and produces a child called an estuary (defined quite simply as “bodies of water where rivers meet the sea”). Estuaries are characterized by water rich in river-delivered nutrients and a range of habitats distinct to the swirling dance of water and sediments as river blends with ocean—mudflats, marshes and, in tropical latitudes, mangrove forests—that are crucial for fish spawning and rearing.

The marriage is so productive that in the United States, 50-75% of the total “marine” fish harvest comes from estuaries (and 80% of the recreational catch). A recent review found similar numbers globally, with about 77% of the marine catch coming from fish that are linked to river flows for at least some portion of their life history.

Given that an estuary is the child of a river and ocean, categorizing all that harvest as “marine” is a bit like an actor effusively thanking his mom during an Oscar acceptance speech and then in closing saying “oh, and I also have a father.”

In other words, rivers are crucial to the majority of the world’s fish harvest.

Crab harvest in Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in the US. Estuaries—where rivers mix with the … [+]

Beyond fish harvests, I recently led an analysis that found that almost one-third of all food globally is derived from rivers. For example, rivers deliver sediment that builds deltas, and deltas produce about 4% of all food in the world (and are home to over 500 million people). The water of rivers irrigates about a quarter of all food production globally.

But, just as with eels on Thanksgiving, rivers are also generally overlooked for their essential role as food. As a result, they are often not managed as the engines of food production that they are.

For example, hydropower dams are built on rivers to produce power at the expense of fisheries and deltas (the dams block migratory fish from reaching spawning habitat and the reservoirs behind dams trap the sediment that deltas need to persist and counteract the rising sea levels and waves which tend to tear them down). And while there are clear alternatives for electricity generation (with wind, solar and batteries now cost-competitive with hydropower), replacing the fisheries and deltas will be much more difficult.

So, on this Thanksgiving Day, let us pause to give thanks for the rivers of food that were essential to both the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims in the early 17th century and that are still essential today. And resolve to protect, restore, and manage them better so that they can provide food long into the future.

Below are some recipes to try with river foods as the Pilgrims may have prepared them (or something close):

Whole roasted eel with sautéd wild mushrooms and leeks

Roasted eel:

· 2 whole eels

· Salt and pepper

· 4-6 tablespoons butter

1. Preheat the oven to 375 F.

2. Once eel has been gutted and cleaned, pat dry (inside and out) and rub thoroughly with salt and pepper. Place the eel into a pan and baste with melted butter (or oil if feeling modern).

3. Roast until skin is browned and crispy and the meat is tender, 25 to 30 minutes. Serve immediately with mushroom and leek sauce.

Mushroom and leek sauce:

· 4 tbs butter

· 1 leek (white part, thinly sliced)

· 1 cup of wild mushrooms, sliced

· Salt and pepper

· 2 tsp apple cider vinegar

1. Melt butter over medium heat

2. Add sliced leek and salt and pepper and sauté and stir until leeks are soft and fragrant

3. Add sliced mushrooms and sauté and stir until cooked through

4. Add vinegar and stir for final 2-3 minutes

5. Drizzle over the roasted eel, salt and pepper to taste

Roasted duck stuffed with onions, sunchokes, grapes, and nuts

· 4 tbs butter

· 1 medium onion, chopped

· ½ cup carrots, sliced

· ½ sunchokes (Jerusalem artichokes), cleaned and cut into small cubes

· ½ cup Concord grapes, halved

· ½ cup walnuts or chestnuts, partly crushed

· Salt and pepper

1. Preheat oven to 350 F

2. Melt butter in a large pan over medium heat and sauté the onion, carrot, and sunchokes; season with salt and pepper

3. Turn off heat and add sunchokes, grapes, walnuts and combine thoroughly

4. As stuffing mixture cools, pat dry the duck.

5. When stuffing is cool enough to handle, stuff into cavity of duck; leave aside a few tablespoons of stuffing

6. Close the duck with toothpicks and score the skin or prick the skin in several places to help release the fat (conventional ducks are very fatty). Rub with salt.

7. Take remaining stuffing mixture and rub across whole duck

8. Place duck on a roasting pan and tie duck legs. Place in the oven for 2 ½ to three hours or until a thermometer inserted at the thickest part reads 165 F.

9. Remove from oven and wait until cool enough to handle

10. Brown the duck by transferring to a baking pan and browning under the broiler.

11. Let duck sit for 5-10 minutes before carving and serving