Rarely have the words harrowing, hopeless, and perilous ever been attached to a wine release. Those phrases are the opposite of what people think when picturing winemaking. Yet, those words perfectly describe the story told in the recently released documentary, Somm: Cup of Salvation, and the accompanying limited-release vintage the story revolves around.

The movie tells the story of Armenian winemaker Vahe Keushguerian and his Quixotic quest to make the first commercial Iranian wine since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 toppled an ages-old industry in the region. Employing subterfuge, sleight of hand, and a passion worthy of cinematic hero Indiana Jones, Keushguerian weaves his way through a complicated country shrouded to most of the Western world. His driving passion is introducing the world to ancient grapes that modern wine has forgotten.

Cup of Salvation shines a light on the fact that Keushguerian is no stranger to tackling larger-than-life projects. The film’s first half highlights Vahe and his daughter Aimee’s work over the last twelve years to resurrect and modernize the wine industry in their war-torn country. Their efforts to introduce the concept of Armenian wine and its wholly unique varietal, Areni, to the wine world is a Sisyphean task that few would undertake.

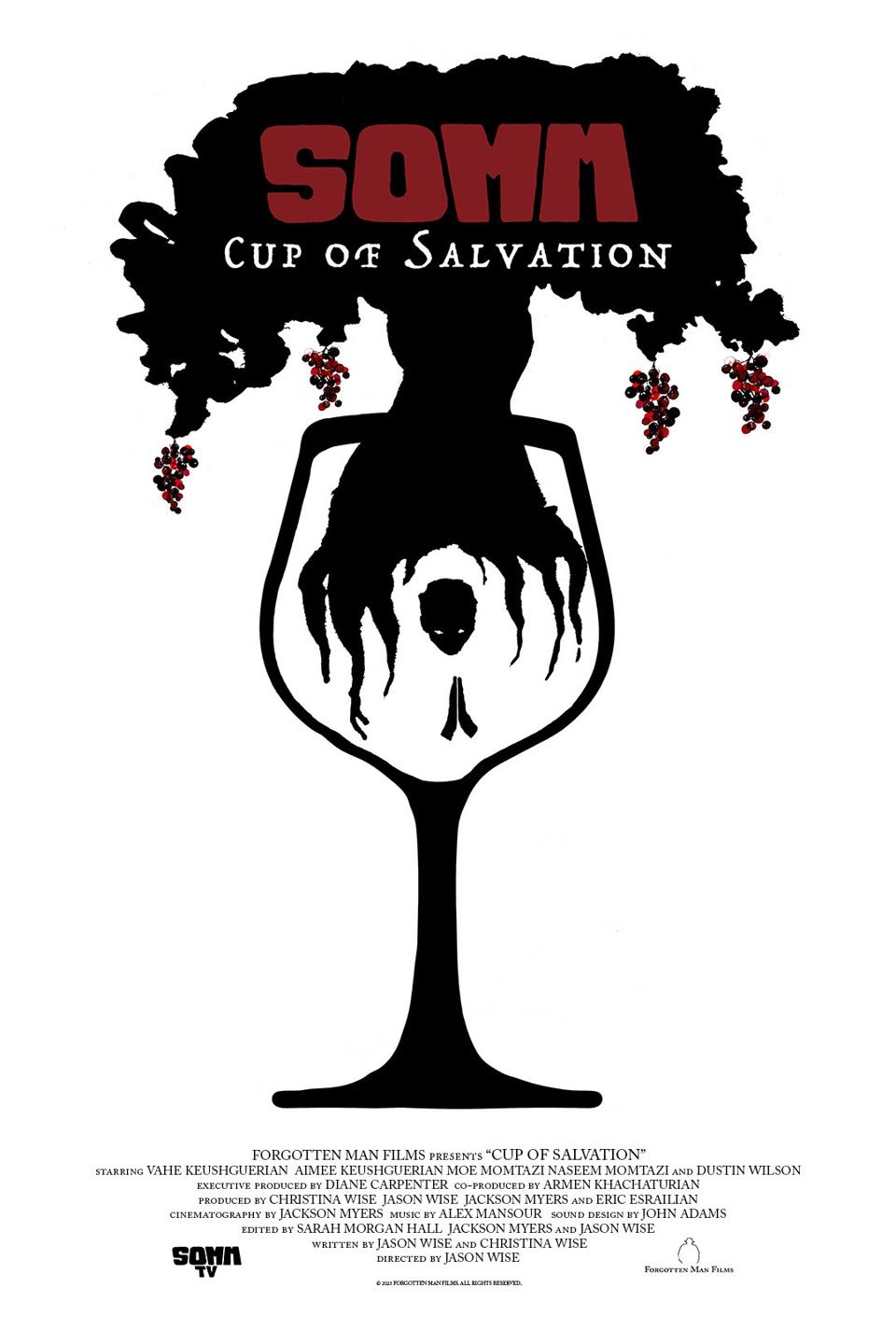

The poster for the movie Somm: Cup of Salvation.

“I knew from the moment I met Vahe that I had to tell his story. There is no other story in the wine world more important right now,” says Jason Wise, the director of Somm: Cup of Salvation. “In my first three Somm films, the stories I told educated viewers about the worldly importance of wine, but this film highlights something incredibly important in a region undergoing significant turmoil. Vahe shines a light on the good that can come from making a beautiful bottle of wine and enjoying it.”

The central concept of the film, and the passion that drives Keushguerian, is that the Persian region of the Middle East, arguably the birthplace of winemaking, has been largely forgotten due to recurring religious and political issues. The winemaker’s work in mapping out the locations of different grape-growing regions is admirable. Ignoring manmade borders, he looks at an area carved up by international borders the way vintners in France survey different appellations inside their own country. He only sees possibilities and a time when the liquid riches of the area can be shared with the world.

Vahe Keushguerian and his daughter Aimee, the central characters of the movie Somm: Cup of Salvation … [+]

He decides to enter Iran under the pretense of buying a truckload of Rasheh grapes for research. His true goal, one he must keep hidden, is to make the first-ever modern Iranian wine. The grapes Keushguerian desires, he believes, may be one of the oldest varietals in the world.

At the time of the Revolution, over five hundred wineries operated inside the country before disappearing. Keushguerian sleuths out some of their remaining vines, hoping there might still be viable winemaking grapes.

Over four days, where he continually looks over his shoulder, he the remains of several old vineyards deep in the Caucasus Mountains, many still tended by their original owners.

The truckload he ships back to his WineWorks winery in Aremina is the base for a wine Master Sommelier Dustin Wilson calls “the most dangerous wine ever made.”

Approximately 15,000 bottles of Moläna Wine were produced for the project, and the chances it will be replicated anytime soon are slim. Named after the 13th-century Islamic scholar Rumi, the bottle calls out that it is a product of Iranian winemaking in exile and offers hope that change, however difficult, is always possible.

The wine is sure to garner significant interest in the wine world, where surprises are few and far between. That is precisely the effect that the director Wise and winemaker Keushuerian hope happens. It is both their fervent desires that this bold project can help shine a light on a region that seems increasingly fraught.

“I believe that this wine will have a huge impact. It’s going to be written about, and it’s going to open talks about not just the wine but also the possibilities it offers,” says Keushuerian.