Cava, the Spanish sparkling wine, has embarked on a relaunching journey to boost its wine’s image and quality. Known among many consumers to offer highly affordable bubbles, others see it as lacking in identity. Will stricter quality rules and better marketing help wine consumers realise that cava is also highly enjoyable?

Cava, Champagne, and Prosecco are the world’s most important sparkling wine brands. Even though they might tell you that they don’t have the same clientele, they are fierce competitors. So, when talking strategies, cava needs to look carefully at what the two others are doing.

Cava’s sales figures for 2023 are promising and show an increase compared to 2022. But volume is not everything; the prices must also be right. Consumers are happy to enjoy a glass of cava at a bargain price. However, many grape growers struggle with poor profitability, which is not sustainable in the long run.

“We need to gain in value and visibility,” says Javier Pagés, president of Cava’s Regulatory Council. “Don’t compare us to Champagne. Cava is different; we have the sun, the light, the Mediterranean, our culture and our own grapes.”

Yes, they do, and these things are well worth mentioning. But getting people to stop comparing cava to champagne will be a challenge. To a greater or lesser extent, all sparkling wines are compared to champagne, for better or worse. Champagne has an edge thanks to its prestige. But the prices are high. All comparisons with Champagne are not in Champagne’s favour. It is an asset to have low prices, as long as they are not too low.

The Cava industry faces challenges and difficult questions regarding the future. End of November 2023, the Regulatory Council organised a major Cava Meeting in Barcelona. Journalists, sommeliers, and wine educators from all over the world, including me, gathered to try to figure out which way forward for Cava.

But first, what is the story behind cava?

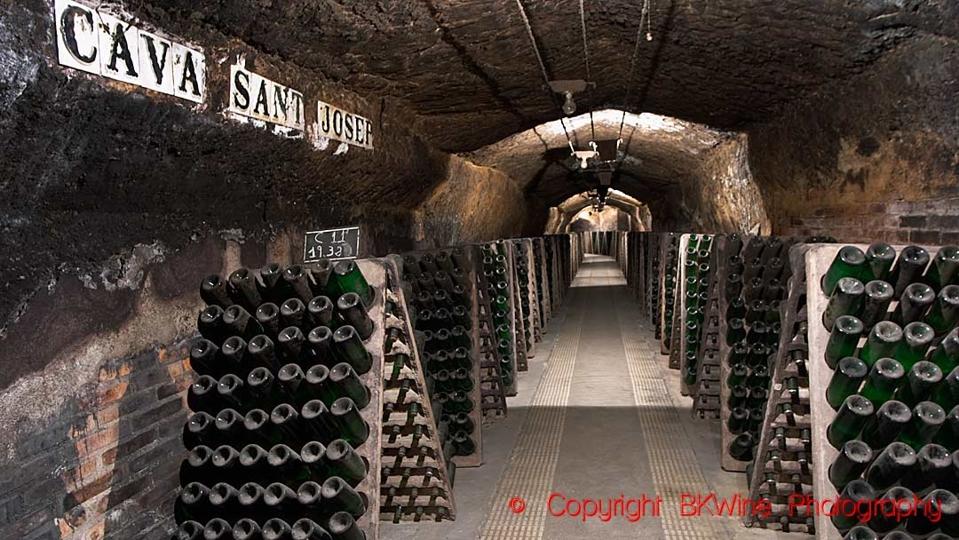

A wine cellar stocked high with ageing bottles of cava at Codorniu in Catalonia, copyright BKWine … [+]

It all started in Penedès in Catalonia, in the town of San Sadurní d’Anoia, close to Barcelona. Penedès was traditionally a red wine region. But the phylloxera (vine louse) in the late 1800s changed all that. When the growers replanted their vineyards, they chose white local grapes instead, macabeo, xarel·lo and parellada. These lent themselves well to sparkling wines, they noted. And the story of cava began.

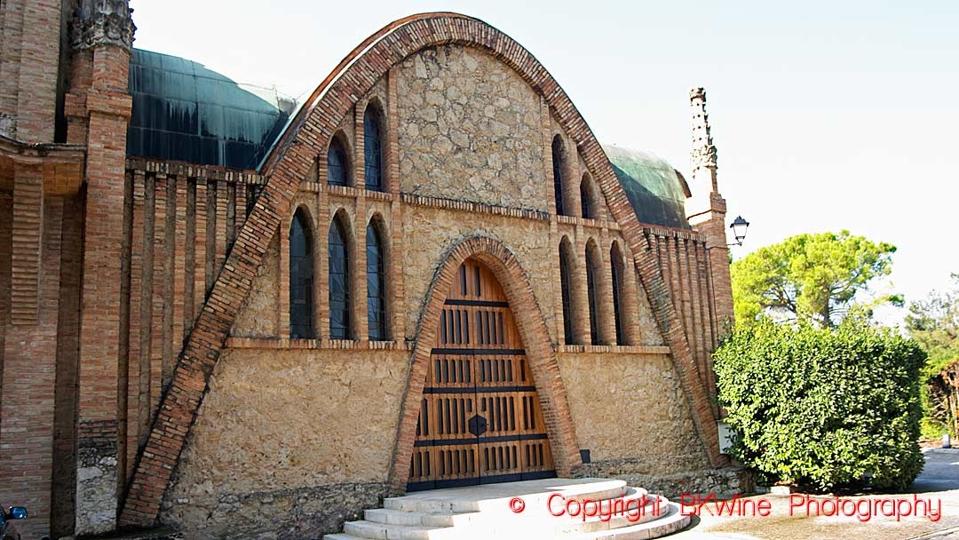

In 1872, Josep Raventòs Fatjó went to Champagne and learned the traditional method with a second fermentation in the bottle. The growers of Penedès adopted the technique. Production grew, and the cava houses built impressive wine cellars – some called them wine cathedrals – inspired by the modernist architecture in vogue at the time. An example is the beautiful cellar at Codorniú.

The sparkling wines produced then were called champan, the Spanish word for champagne, or xampan, the Catalan word. No one minded at the time, but that would eventually change. In 1928, the Mestres family (a house specialising in long-aged cava) began to call their wines cava instead of xampan. In 1959, the word cava was officially used for the first time.

Cava is made with the “traditional” method, fermenting in bottle and then disgorged, copyright … [+]

1972, the Consejo Regulador de los Vinos Espumosos was created, which approved the designation “cava” for Spanish sparkling wines. In 1986, the same year Spain joined the European Union, the Cava region was demarcated, and the traditional method became mandatory. DO Cava was born.

The total vineyard surface for Cava is almost 95,000 acres, producing around 250 million bottles annually. Large houses dominate the industry. They often own vineyards but also need to buy grapes from one or several of the almost 6,000 grape growers. The three local grapes, macabeo, xarel-lo and parellada, today account for nearly 82% of the plantings.

(For comparison, Champagne has 84,000 acres and makes just over 300 million bottles, Prosecco has 69,000 acres and produces around 600 million. If you think low harvest yields are essential for the character of a wine, you should not drink Prosecco.)

Criticism within and outside the cava industry has been frequent in recent years. It is about cava not having high enough quality requirements, not enough focus on terroir, big houses that prevent the small ones from succeeding, and too low grape prices. Some (few but famous) producers left DO CAVA in protest in 2018 and started their own brand, Corpinnat.

One of the “modernista” buildings at the Codorniu cava winery in Catalonia, copyright BKWine … [+]

DO Cava had to do some soul-searching. Stricter new rules were introduced for premium cava to motivate the producers to raise the quality bar and, thus, the wine’s reputation. The new regulations emphasise long ageing on the lees to provide complexity and better overall ageing capacity.

There are now two kinds of cava: cava de guarda and cava de guarda superior. This latter is, in turn, divided into three categories: Reserva, Gran Reserva and Paraje Calificado.

Cava de Guarda dominates with 86 % of sales. Within the category, the producers’ ambitions and philosophies vary, and you can indeed find very inexpensive cava, but not only. Spend just a bit more on a bottle, and you will discover a lot of excellent and high-quality cava. Cava de Guarda has a 9-month minimum of ageing on the lees.

Cava de Guarda Superior has more extended ageing on the lees and other requirements. The vines must be at least ten years old; the permitted yield is lower, and all wines must have the vintage on the label. All Guarda Superior must have organic certification from the 2025 vintage.

Reserva has been aged at least 18 months in bottle, and gran reserva at least 30 months. Paraje Calificado is a particular category within Guarda Superior, where the wine comes from a selected vineyard often mentioned by name on the label. The wine is aged 36 months or longer. This is now the most prestigious category of Cava.

Preparing to taste wines at the Cava Meeting Conference in Catalonia, copyright BKWine Photography

Guarda Superior accounts for 4.5% of cava sales. Even if this is a small part, these wines are essential. They will fetch higher prices, and a wine region needs wines with high prices to gain respect. “Guarda Superior is small volumes but a positive addition to Cava DO”, says Javier Pagès.

The Cava industry is dominated by houses such as Codorníu and Freixenet (now owned by Germany’s Henkell). Three Cava houses account for more than 50% of the production. Some people see this as a problem, but if it is a problem, it is not unique to Cava. Do the big ones prevent the small producers from succeeding?

It is indeed the low prices of the big houses on the export market that have caused the wine’s reputation to drop. And in negotiations in the Cava Regulatory Council, the power struggle is, perhaps, uneven. Comparisons can be drawn with Champagne (except for the low prices).

But the big ones have the quantities to reach countries and markets worldwide. They are brand builders; without them, cava would not be as well-known as it is. “A powerful brand is value,” says Pedro Ferrer, CEO of Freixenet Group, “you need strong brands.”

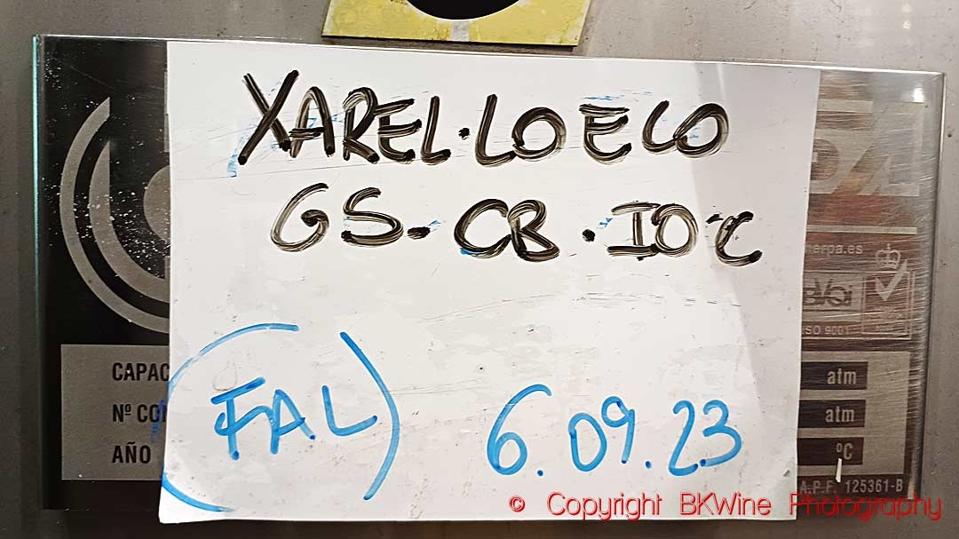

Smaller producers attract a different consumer group, those looking for a story, personality, and long ageing. Sommeliers and wine enthusiasts today are constantly looking for novelties and interesting niche wines. This is where the small ones come in. The smaller you are, the more specialised you must be to stand out. Maybe with a cava from 100 % xarel-lo, a grape with all the makings of a new star.

Xarel-lo in a tank in a winery in Catalonia, one of the important grapes in cava, copyright BKWine … [+]

The low grape prices are a real problem. The Cava houses that buy the grapes from the growers pay too little because they cannot sell their cava at high enough prices. The grape growers suffer from poor profitability, and the low prices damage the reputation of cava. There should be a way out of this, but how? Cava exports 70% of its production, and the numbers speak for themselves. In terms of value, Spain is far, far behind sparkling wines from Italy and France.

The poor Spanish value applies to Spanish wines in general, not just sparkling wines. In 2023, statistics show that Spain exported 21 million hectolitres of wine worth 3 billion euros. Italy exported the same amount in volume but for 7.8 billion euros. And France exported 14 million hl of wine worth 12.3 billion euros.

The Spanish must get better at selling themselves and thus improve the export value.

“DO Cava does not believe in itself; we are too humble,” says Marc Morillas from Morillas Brand Design. “We are very bad at selling ourselves, and that applies to other products as well. Italians are better at telling stories. We must invest in what makes us different.”

He is right. The Spanish have something to learn from the Italians. Thanks to clever marketing, they have had incredible success with their prosecco, not least in the United States.

Some of the speakers at the Cava Meeting Conference in Catalonia, copyright BKWine Photography

“Prosecco has taken an iron grip on the American market,” says Doug Frost, MW, MS, and specialist in the American wine industry. Prosecco sales to the US increased by 6% to 134 million in 2022. Cava shipped 21.6 million bottles in the same year, down 8.85% from 2021. “Cava is seen more in grocery stores, and prosecco and champagne in restaurants. The young are not interested in wine, but they drink sparkling, but cava has not benefited from that,” Doug continues.

If you look around in different countries, you will see that low-price cava is often sold at the same prices as or cheaper than prosecco, even though cava is made by the more expensive traditional method with a second fermentation in the bottle and at least nine months of ageing. Prosecco is essentially a volume product, quickly produced with very high yields and a second fermentation in a pressure tank. But do consumers know or even care? Probably not. Prosecco has an image and packaging that attracts the young. It is all about marketing.

If large volumes of cheap cava are no longer sustainable, would the solution be to drastically reduce production with higher prices as a result? This idea came up during the Cava Meeting. It is an interesting thought, but it is based on accepting the loss of a large number of customers who will not pay the higher prices.

A wine cellar stocked high with ageing bottles of cava at Pares Balta in Catalonia, copyright BKWine … [+]

“We have to decide what to sell,” says Jaume Vial, sales manager at Cava Mestres. “Now we try to make everyone happy.”

For Jaume Vial and many others in the cava industry, the path to success is through gastronomy.

Here again, the Italians have a significant advantage as Italian restaurants are everywhere worldwide. But cava does not need Spanish food. “One of the main goals,” says Javier Pagès, “and the current challenge, is to show that cava is the gastronomic drink par excellence, infinitely versatile to match every cuisine.”

With more and more sommeliers and top restaurateurs offering cava reserva and gran reserva in their restaurants, influential wine enthusiasts will discover these more ambitious cavas. They will spread the word and improve the image of cava in the process. At least that’s the idea. And maybe spread some Spanish culture as well. Rafael Antoin, food influencer and Cava ambassador, regrets that “we are missing to show people our cava culture; it is not present among the young.” Well, it is time to remind them.

Keep an eye out for more Cava articles here, including producer recommendations.

—Britt Karlsson